90. The English Saint Michael Line (Part 2)

- M Campbell

- 2 days ago

- 44 min read

As the Saint Michael alignment threads its way toward Avebury, it weaves through a landscape shaped by myth, history, and sacred geometry. From Cornwall to Wiltshire, this route passes not only through prehistoric sites, ancient hillforts, and medieval churches, but also through a pattern of dedication to Saint Michael, a devil or dragon slayer, and, intriguingly, to Saint Mary and occasionally Saint George, another dragon-slaying saint. These sites, seemingly varied in purpose and age, are connected by something as simple, and as mysterious, as their position in the landscape.

The research that has been done on various Saint Michael alignments has been mostly outside academia. Katherine Maltwood alluded to the English line in her Guide to Glastonbury's Temple of the Stars (1935), which was picked up by John Michell in his View Over Atlantis in 1969. A few years earlier, in 1966, Jean Richer had published his Géographie Sacrée du Monde Grec, which examined alignments between sacred Greek places, and in 1977 his brother Julien wrote about an alignment through the Greek islands which could be extended all the way to the Mont Saint-Michel and beyond, to Saint Michael’s Mount and Skellig Michael. More recently, Lucas Mandelbaum (The Axis of Mithras: Souls, Salvation, and Shrines Across Ancient Europe, 2016), and Yuri Leitch (The Terrestrial Alignments of Katherine Maltwood and Dion Fortune) have contributed to the research.

One of the things that makes this alignment remarkable is not just the density of significant sites along it, but also its precision. Many of these sites fall along a near-perfect straight line stretching across south-west England, linking the coastal sanctuary of Saint Michael’s Mount with the great Neolithic complex of Avebury. And the alignment doesn’t stop there. It continues beyond Avebury toward some of Britain's most enigmatic ancient sites, hinting at a long-forgotten logic that may stretch back thousands of years. In Part One, we traced the route from Saint Michael's Mount to Avebury. In this second part, we revisit the key sites between Cornwall and Wiltshire, give context for the possibility of such an alignment by looking at evidence for a widespread ancient landscape geometry, speculate on the significance of Saint Michael, and look what lies beyond Avebury.

A recap of the alignment between the Cornish coast and Avebury

The English Saint Michael alignment is path that begins in Cornwall, at the dramatic tidal island of Saint Michael’s Mount, and at a cairn close to Land's End, Carn Lês Boel, and stretches all the way to the massive henge at Avebury. Roughly bissecting the south-west of England, the alignment passes through:

Relubbus and the Giant’s Quoit at Carwynnen,

The Hurlers stone circles on Bodmin Moor, one of Cornwall’s most enigmatic prehistoric clusters,

Restormel Castle, a once important Norman castle, perfectly circular in shape,

The legendary Glastonbury Tor, its ruined Saint Michael’s tower rising from the summit, with the Tor itself seemingly oriented toward the alignment,

Burrow Mump, another sacred hill with a ruined chapel dedicated to Saint Michael, on top,

Athelney, a former island in the Somerset Levels with deep historical significance, famously the hiding place of King Alfred,

Cadbury Castle in Devon, a lesser-known hillfort overlooking the Exe valley, distinct from its more famous Somerset namesake.

From here, the alignment moves northeastward to Avebury, passing several other hillforts and prehistoric sites: Lethen Castle, Cambria Farm, Roundway Down (Oliver’s Castle), and St Stephen’s Beacon. As we map these sites, another curious fact emerges.

There are two nearly parallel lines, each beginning at the Cornish coast and converging on Avebury. One originates at Carn Lês Boel, a prehistoric cliffside outcrop near Land’s End. The other begins at Saint Michael’s Mount. Both follow almost identical azimuths, incorporating ancient and medieval sites, and eventually continue toward Bury St Edmunds and the Norfolk coast. Glastonbury Tor and Burrow Mump, perfectly aligned with Avebury, fall slightly off the line departing from Saint Michael’s Mount, but are exactly on the line from Carn Lês Boel.

Both Glastonbury and Athelney were once islands, rising from the marshy landscape of the Somerset Levels, and both are steeped in spiritual and historical lore. Their placement on this alignment adds another layer of mystery. The images below show sections of the alignment, with a little more detail, starting with the south-west and progressing up towards the north-east.

The images show two lines, which follow a similar azimuth and incorporate major ancient and medieval sites, running almost parallel alongside each other, eventually gradually merging as they approach Norfolk. While many of the important sites were placed on or very close to the line drawn from Saint Michael's Mount to Avebury, others, which are precisely aligned with each other and Avebury, such as Burrow Mump and Glastonbury Tor, are on a line set slightly apart, which begins at Carn Lês Boel, a prehistoric site on a cliff near Land's End, and then proceeds to Avebury, which, being such an enormous site, can accommodate both lines passing through it. On the diagrams above, the line beginning at Saint Michael's Mount is in red and the other in green. On the Google Earth screenshot below, just the main sites are marked along the first leg of the line.

A line linking Carn Lês Boel with the centre of Avebury goes straight through key sites such as Glastonbury Tor and Burrow Mump, which both have ruined chapels dedicated to Saint Michael on their summit. This is illustrated with the images below, with the line in yellow.

To calculate the azimuth of these lines, only the most important sites were taken into account, which were Saint Michael's Mount, The Hurlers, Burrow Mump, Glastonbury Tor and Avebury. To establish a baseline, the azimuth from Saint Michael’s Mount to several key sites was taken from Google Earth:

Saint Michael’s Mount → The Hurlers: 58.31°

Saint Michael’s Mount → Burrow Mump: 58.64°

Saint Michael’s Mount → Glastonbury Tor: 58.70°

Saint Michael’s Mount → Avebury (centre): 58.82°

Saint Michael’s Mount → Avebury (south-east side): 58.87°

Saint Michael’s Mount → Bury st Edmunds (Cathedral): 58.9°

These sites form a strikingly linear pattern, all falling within a fraction of a degree from one another. Notably, the alignment includes several Saint Michael-dedicated sites: Glastonbury Tor, Burrow Mump, and Saint Michael’s Mount, and a church dedicated to St Michael in Othery. There are also churches dedicated to St George, another dragon slayer, and three to Saint Mary, and other churches with various other dedications, included if they were placed on the line. The gradual increase in azimuths from Saint Michael’s Mount to Bury St Edmunds ranging from 58.31° to 58.90° is not random, but reflects the expected geometry of a great-circle alignment across a curved Earth.

If we take Carn Lês Boel as an alternative starting point, we get similar azimuths to Avebury and Bury St Edmunds.

Carn Lês Boel → Glastonbury Tor (centre): 59.13°

Carn Lês Boel → Burrow Mump (centre): 59.12°

Carn Lês Boel → Avebury (centre): 59.12°

Carn Lês Boel → Bury St Edmunds: 58.92°

Carn Lês Boel → The Hurlers: 59.46°

Avebury

Avebury is a huge henge containing three stone circles, one of which is the largest of its kind. Surrounding it is a cluster of ancient sites, from barrows to smaller stone circles, hillforts and mounds, such as the enigmatic Silbury Hill. Despite being of the most important megalithic sites of all, Avebury has been vandalised for centuries. The tiny chapel which stands in its centre is partly made of stones from the circle, as is some of the village. Religious belief has been a driving force in the destruction of the stones, most of which are gone now. The chapel can be taken as a celebration of this ancient temple, or as a celebration of the henge's submission to a different world view. It is not necessarily a view that is much different to what neolithic farmers, who changed the landscape from forests to fields, might have upheld. But it is perhaps at odds with an older view, which might encourage the protection and admiration of the natural world, and which a network of ancient sites might have once served. It is tempting to imagine a time, when forests still covered much of these islands, and when a veneration for Mother Earth might have been a major factor in people’s approach to their environment. Her demotion may have paved the way for religions that allowed both the destruction of the natural world and, eventually, the destruction of megalithic structures. It could perhaps have coincided with agriculture and deforestation on a large scale. If henges and stone circles are, as archaeologists suggest, contemporary with the introduction of farming, then perhaps these great engineering feats of the neolithic had a similar purpose to the building of great churches and abbeys on the sites of great pagan temples had: to appropriate and dominate a place already considered sacred by a previous culture. The presence of the chapel inside Avebury begs the question: what makes a place sacred, other than the idea that it just always has been?

It is interesting to compare the building of a chapel within Avebury to the churches and chapels on top of other important places along the alignment such as Glastonbury Tor and Burrow Mump. Surely some of the churches we find along the way, even the ones not on hill tops, must mark the spot of long since destroyed pre-historic landmarks, and as such it is important to consider them as significant as potentially the remains of megalithic structures, in understanding the landscape. This must be especially true of churches dedicated to Mary, or Roman temples dedicated to Venus for example, or other important female religious figures, who might walk in the moccasins of long gone Mother Earth deities. As for the figure of the Archangel Michael, who plays such an important in this neolithic landscape, perhaps he too walks along a path once trodden by a son or consort of Mother Earth, like Horus or Osiris to Isis, or Attis to Cybele, Jupiter to Juno or Venus; Zeus to Hera or Aphrodite, or Adonis to Aphrodite and Persephone, Dumuzid to Inanna / Ishtar, Shiva to Parvati. In this case there may be a connection to the planets Mars and Venus. Or perhaps some of the sites associated with the Archangel Michael were once related to those sites now dedicated to Mary as brother and sister, such as Apollo to Artemis, sun and moon. Like the Archangel Michael, several of these male deities are associated with hill tops, mountains and rocks, such as Attis, Jupiter and Shiva for example. In France and Italy, in fact, many hills are still known by variations on Jupiter’s name. Unlike Jupiter, however, the Archangel Michael has no gender, although he/she is mostly depicted as a good-looking young man, like Adonis or Attis, gods of vegetation.

The destruction of so many stones at Avebury is a reminder that for a very long time, people have not valued ancient sites and have got away with destroying them, and still do. William Stukeley writes about the destruction of Avebury:

Just before I visited this place, to endeavour at preserving the memory of it, the inhabitants were fallen into the custom of demolishing the stones, chiefly out of covetousness of the little area of ground, each stood on. First they dug great pits in the earth, and buried them. The expence of digging the grave, was more than 30 years purchase of the spot they possess’d, when standing. After this, they found out the knack of burning them; which has made most miserable havock of this famous temple. One Tom Robinson the Herostratus of Abury, is particularly eminent for this kind of execution, and he very much glories in it. The method is, to dig a pit by the side of the stone, till it falls down, then to burn many loads of straw under it. They draw lines of water along it when heated, and then with smart strokes of a great sledge hammer, its prodigious bulk is divided into many lesser parts. But this Atto de fe commonly costs thirty shillings in fire and labour, sometimes twice as much. They own too ’tis excessive hard work; for these stones are often 18 foot long, 13 broad, 16 and 6 thick; that their weight crushes the stones in pieces, which they lay under them to make them lie hollow for burning; and for this purpose they raise them with timbers of 20 foot long, and more, by the help of twenty men; but often the timbers were rent in piecs.

They have sometimes us’d of these stones for building houses; but say, they may have them cheaper, in more manageable pieces, from the gray weathers. One of these stones will build an ordinary house; yet the stone being a kind of marble, or rather granite, is always moist and dewy in winter, which proves damp and unwholsom, and rots the furniture. The custom of thus destroying them is so late, that I could easily trace the obit of every stone; who did it, for what purpose, and when, and by what method, what house or wall was built out of it, and the like. Every year that I frequented this country, I found several of them wanting; but the places very apparent whence they were taken. So that I was well able, as then, to make a perfect ground-plot of the whole, and all its parts. This is now twenty years ago. ’Tis to be fear’d, that had it been deferr’d ’till this time, it would have been impossible. And this stupendous fabric, which for some thousands of years had brav’d the continual assaults of weather, and by the nature of it, when left to itself, like the pyramids of Egypt, would have lasted as long as the globe, must have fallen a sacrifice to the wretched ignorance and avarice of a little village unluckily plac’d within it; and the curiosity of the thing would have been irretrievable.

Such is the modern history of Abury, which I thought proper to premise, to prepare the mind of the reader. (1)

Avebury as the snake

William Stukeley puts forward an interesting theory: that Avebury is part of a gigantic snake, in the landscape. Avebury itself is described as a "serpentine temple" or "dracontia".

Names or words are necessary for the understanding of things; therefore 1. The round temples simply, I call temples; 2. Those with the form of a snake annext, as that of Abury, I call serpentine temples, or Dracontia, by which they were denominated of old; 3. Those with the form of wings annext, I call alate or winged temples. And these are all the kinds of Druid temples that I know of. We may call these figures, the symbols of the patriarchal religion, as the cross is of the christian. Therefore they built their temples according to those figures. (2)

Stukely refers to Avebury as:

Abury, the most extraordinary work in the world, being a serpentine temple.

Adding:

The figure of the temple of Abury is a circle and snake. Hakpen, another oriental word still preserved here, meaning the serpent’s head. The chorography of Abury. A description of the great circle of stones 1400 foot in diameter. Of the ditch inclosing it. The vallum form’d on the outside, like an amphitheater to the place. This represents the circle in the hieroglyphic figure. Of the measures, all referring to the ancient eastern cubit which the Druids us’d. (3)

Stukely identifies the head of this snake as Hakpen Hill.

In order to put this design in execution, the founders well studied their ground; and, to make their representation more natural, they artfully carry’d it over a variety of elevations and depressures, which, with the curvature of the avenues, produces sufficiently the desired effect. To make it still more elegant and picture-like, the head of the snake is carried up the southern promontory of the Hakpen hill, towards the village of West Kennet; nay, the very name of the hill is deriv’d from this circumstance, meaning the head of the snake;

The tail of the snake is associated with Beckhampton:

the tail of the snake is conducted to the descending valley below Bekamton.

Stukely adds:

Thus our antiquity divides itself into three great parts, which will be our rule in describing the work. The circle at Abury, the fore-part of the snake, leading towards Kennet, which I call Kennet-avenue; the hinder part of the snake, leading towards Bekamton, which I call Bekamton-avenue; for they may well be look’d on as avenues to the great temple at Abury, which part must be more eminently call’d the temple.

Confusingly, however, Stukely also refers to the head of the snake as the site at Overton Hill:

the temple on Overton-hill, which is properly the head of the snake:

However, the name of Hakpen Hill is associated, for Stukely with serpents, etymlologically.

To our name of Hakpen alludes אחים ochim call’d doleful creatures in our translation, Isaiah xiii. 21. speaking of the desolation of Babylon, “Wild beasts of the desert shall lie there, and their houses shall be full of ochim, and owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there.” St. Jerom translates it serpents. The Arabians call a serpent, Haie; and wood-serpents, Hageshin; and thence our Hakpen; Pen is head in british.

עכן acan in the chaldee signifies a serpent, and hak is no other than snake; the spirit in the pronunciation being naturally degenerated into a sibilation, as is often the case, and in this sibilating animal more easily. So super from υπερ, sylva from υλη, sudor, υδωρ. So our word snap comes from the gallic happer, a snacot fish from the latin acus, aculeatus piscis. And in Yorkshire they call snakes hags, and hag-worms. Vide Fuller’s Misc. IV. 15.

The temple that stood here was intended for the head of the snake in the huge picture; and at a distance, when seen in perspective, it very aptly does it. It consisted of two concentric ovals, not much different from circles, their longest diameter being east and west. By the best intelligence I could obtain from the ruins of it, the outer circle was 80 and 90 cubits in diameter, the medium being 85, 146 feet. It consisted of 40 stones, whereof 18 remained, left by farmer Green; but 3 standing. The inner circle was 26 and 30 cubits diameter, equal to the interval between circle and circle.

The idea of Avebury as a snake is interesting in the context of a Saint Michael alignment. If we think of the line emanating from Saint Michael's Mount, it becomes almost like the spear which the archangel is so often shown holding and which the archangel directs into the dragon (or devil's) mouth. While the idea seems fanciful and anachronistic, it is worth considering. Many ancient societies had deities which showed a snake being speared in the mouth, such as ancient Egypt, Set spearing a giant serpent in the head, as one example, or Marduk and Tiamat as another. In this respect, the comparison between the Archangel Michael, and other deities, from Saint Patrick to Saint George, to Set, and Horus, and many others, with the constellation Ophiuchus is useful. this constellation features a tall figure standing above the constellation Scorpio. Some aspects of this stellar dual are reflected in the Archangel Michael images, in which the archangel carries a pair of scales in the hand where, in the sky, the constellation Libra fits. Another intriguing aspect is the direction of the spear towards the mouth of the dragon, serpent or devil, as this is where one of the brightest stars can be found, Antares.

Below, images show the constellation Ophiuchus, as drawn by H.A. Rey, with various divine figures from different traditions: the hermaphrodite of alchemy, Horus and crocodile, the churning of the Milky Ocean, the Anti-Christ and Leviathan, Jesus treading the beasts, Marduk and Tiamat, Thor and the Midgard serpent, Saint Patrick and snakes, Set and Apep, Aztec deity, Saint Michael, and Saint George. It is certainly possible that a similar dragon or serpent taming divine figure existed for the megalith builders, or their ancestors.

However, the scale of the alignment doesn't really work with the albeit gigantic snake at Avebury.

The way Saint Michael and similar figures are depicted, slaying a dragon, standing on serpents, or triumphing over demonic forces, suggests a deep-rooted connection to the constellation Ophiuchus, the Serpent-Bearer. This constellation, though not part of the twelve-sign zodiac, plays a crucial role in the celestial sphere. One foot of Ophiuchus lies on the ecliptic (the apparent path of the Sun), while the other is set in the Milky Way. This positioning makes it a cosmic intermediary, bridging the solar journey with the wider celestial domain. Various divine figures have been associated with its features, from the Virgin Mary to Horus, reinforcing its symbolic signficance across different cultures.

The prevalence of sun gods throughout history suggests that Saint Michael and Saint George may stem from a far older solar deity tradition. Many ancient gods, including Mercury, Jupiter, Attis, and Adonis, had seasonal roles tied to the equinoxes and solstices. Early Christian art reflects this solar influence, with Christ depicted standing frontally over defeated beasts, mirroring earlier depictions of solar deities vanquishing the forces of darkness.

A striking example of this battle between light and darkness comes from Egyptian mythology, where the sun god Ra faces his eternal adversary, Apep (Apophis). Apep, a great serpent representing chaos and disorder, was said to lurk in the underworld, waiting to ambush Ra as he journeyed through the night. Ra, as the bringer of light and upholder of cosmic order (Maat), was Apep’s greatest foe, earning the serpent the title "Enemy of Ra" and "Lord of Chaos."

Myths tell that each night, Apep attempted to prevent the sun’s rebirth, hiding in the western mountains of Manu or lurking just before dawn in the Tenth Region of the Night. The idea of a primordial chaos serpent, subdued by a solar god, echoes through other traditions as well. In Mesopotamia, Marduk slays the sea-dragon Tiamat; in Norse mythology, Thor battles the Midgard Serpent; and in Hinduism, Indra conquers the serpent Vritra to release the waters of life. The persistence of this motif across cultures suggests a fundamental human narrative: the triumph of light over darkness, order over chaos.

The Sun has always been regarded as the source of life, controlling the ripening of crops and sustaining human civilisation. In Ancient Egypt, Ra was not only the sun god but the creator of the universe, a deity so influential that he became the "King of the Gods." This reverence for the Sun extended far beyond Egypt. The Hindus worship the Sun as Surya, the Incas revered Inti, and the Japanese associated the Sun with the goddess Amaterasu.

This universal veneration of the Sun aligns with the sacred geography of Britain. The Saint Michael alignment appears to be a direct expression of this ancient solar belief system. Just as Ra’s spear of light overcame Apep’s darkness, so too does the landscape of the Saint Michael alignment reflect a similar symbolic battle.

The idea that the Saint Michael alignment encodes a cosmic battle between order and chaos finds support in the landscape itself. Stukeley as ressembling description of Avebury and its surroundings as a serpent, coiled within the landscape. The significance of this becomes clearer when considering the movement of the Sun along the alignment.

A parallel myth can be found in Slavic mythology, where the thunder god Perun battles the great serpent Veles. The enmity between these gods stems from Veles’s theft of Perun’s cattle, wife, or child. Veles, a deity of the underworld and water, slithers up the world tree (axis mundi) in an attempt to challenge Perun, the ruler of the sky. In response, Perun attacks Veles with his lightning bolts, driving him back down to the underworld. The storm myth reflected seasonal cycles, the dry periods were seen as the result of Veles’s disorder, while storms and rain symbolised Perun’s triumph, restoring balance.

This cyclical myth of a god battling chaos each year mirrors the annual solar journey. If we consider Stonehenge as the north celestial pole, then perhaps Avebury represents the great serpent coiling around it, a reflection of Ophiuchus around the celestial sphere. Just as Veles is struck down but rises again, the serpent of Avebury is symbolically defeated each year by the sun’s movement along the Saint Michael alignment.

This archetypal battle is not confined to Europe and the Near East. In the Americas, the Aztecs believed their sun god Huitzilopochtli fought the darkness each night, and only through ritual sacrifice could the sun be reborn. In Australia, Baiame, the sky deity, subdued the great serpentine forces of the underworld to create the ordered world. In New Zealand, the Māori god Tāne separated his parents, Sky Father (Rangi) and Earth Mother (Papa), to bring light into the world, another symbolic victory of order over primordial darkness.

This alignment is not just a geographical curiosity but a relic of an ancient worldview in which sacred landscapes mirrored celestial events. The association of Saint Michael, Ophiuchus, and the Sun’s movement reveals a hidden solar theology underlying the placement of these sites. Whether in Egypt, Mesopotamia, or Britain, the same archetypal struggle is recorded: the Sun God’s victory over the primordial serpent of chaos. The presence of megalithic and Christian sites along this line suggests an unbroken tradition, adapting and evolving over millennia, yet always reflecting the same fundamental truth, the eternal battle between light and darkness.

By tracing the Saint Michael alignment through Britain’s sacred landscape, we uncover not just an old pilgrimage route, but a cosmic story embedded in stone, sky, and time.

Beyond Avebury

The St Michael’s Mount to Avebury line extends well beyond Avebury, to the north-east, and, when it comes to the Norman layer, it is mostly Mary’s. The first stop is Overton Down, mentioned by Stukely in relation to his Avebury serpent, then Rockley Down round barrows, the Polisher Stone, Ogbourne St George parish church, near Seven Barrows, then Sugar Hill bowl barrow, Segsbury Camp (also called Letcombe Castle), and St Mary the Virgin churches at Long Wittenham and at East Hendred. Then it is the site of the Dorchester rings henge and cursus, of which almost nothing is left. Beyond Dorchester, Mount Farm timber circle is also gone, but the church of Saint Catherine and Leonard at Drayton St Leonard and the church of St Michael and All Angels in Aston Clinton are both right on the line. Near the line are the churches of St Mary at Weston Turville and the church of St Michael at Halton, and the church of St Mary the Virgin at Drayton Beauchamp. Then the line runs close to the church of St Mary’s at Pitstone, and the Northfield settlement ancient village and the causewayed enclosure on Pitstone Hill, then near the church of St Mary the Virgin at Ivinghoe, and through Ivinghoe Beacon Hillfort and barrows, then near the church of St Mary Magdalen at Whipsnade, and the church of St Mary the Virgin at Kensworth, and a mile from St Mary’s church in Luton, and a mile from Waulud’s Bank Henge, and near St Mary Magdalen’s church at Great Offley, and St Mary’s church in Hitchin, then St Mary’s church and nearby St Michael’s church in Letchworth Garden City (the city might be modern but the churches are old). Also nearby are Wilbury Hill Hillfort, Letchworth Cursus, Norton Henge, and St Mary’s parish church, and some long gone barrows under the A505 and the Bygrave barrows. Then, closer to the line again is a church of St Mary’s in Wallington, another at Therfield, a church of St Mary and John at Hinxton and near the church of St Mary’s at Little Abington. The line goes near several more churches of St Mary at Kirtling, Lidgate, Denham, Westley and Ickworth. Then we come to Bury St Edmonds Abbey and Cathedral, situated on a hill called Angel Hill. A little further on, the line goes through a church of St Mary at Rickinghall and another at Rushall, then through the Churches of St Mary’s in Denton, Bungay, Ellingham, Haddiscoe, and Ashby. At Bungay the brown line from Carn Lês Boel to the north side of Avebury extended goes right through the castle in the town, a ruined Norman building on a mound, named Bigod. The line also goes through a Church of St Michael’s at Stockton. There are quite a few churches of Michael and Mary near the line. Below are some images related to the line beyond Avebury.

The Long Wittenham area has many Bronze Age traces: enclosures, pottery, and trackways. The village is right on the Thames, at a very interesting point, where the river splits into two separate parts which meet again, and then create a huge meander, after which there is a confluence with another river, just south of Dorchester on Thames. This place has the curious characteristic of having almost exactly 1,000 minutes of daylight at the summer solstice. For 2023 for example, the hour count is 16:40:03. Skellig Michael is on a similar latitude.

Dorchester on Thames is full of ancient sites, or the traces of ancient sites. The extended Michael Mount to Avebury line goes through the now gone Dorchester Rings. The website Ancient-wisdom.com says: “The Henge and associated monuments were built over an existing Cursus monument, something found at other sites such as Thornborough and Stonehenge (which has the same circumference). ” It’s hard to believe this site was allowed to be destroyed, but it was, for the gravel industry.

An archaeological report states:

From 1946 to 1952. excavations were undertaken in advance of destruction by gravel workings of a series of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age monuments at Dorchester-on-Thames, Oxon. These included a long enclosure, a cursus, a double ditched henge, pit circles and ring ditches with primary and secondary cremation burials and a notable Beaker burial. (...) By the early 1950s much of the Neolithic complex had been quarried for gravel, and other adjacent areas subsequently were dug away. In 1981 the construction of a bypass led to the excavation of further surviving parts of the complex: site 1, a long D-shaped enclosure incorporated in the southern end of the cursus, and sites 2, 3 and 4.1

Then the line goes on to the church of St Michael in Aston Clinton, then between two hurches of St Mary at Ivinghoe and Pitstone, Beacon hillfort, the church of St Mary in Letchworth, the church of St Mary and St John at Hinxton, Bury St Edmonds.

Bury St Edmunds is an ancient major religious site, though the parish church of St James only became a cathedral quite late on, in 1914. A once king of East Anglia, Edmund, who was killed by the Danes, became a martyr because he refused to give up his religion when pressed by the ‘heathens’. The brave man’s remains were taken to Bury St Edmunds, and a shrine was built. The king was made a saint and the town took his name. Fans of Bernard Cornwell and his Last Kingdom series might remember the scene when the king is filled with arrows after trying to convince the Danes about the miracle of Saint Sebastian. This is the second time a place from the Last Kingdom series has appeared along the St Michael Mount - Avebury line, the first one having been the Isle of Athelney, where King Alfred took refuge in the marshes.

Bury St Edmunds must already have been important if the remains were taken there, in the same way that Durham must already have been important if the remains of that other major saint, Cuthbert, were taken there. Along the way to Bury St Edmunds (called Bedricsworth or Beodericsworth at the time), the body was temporarily placed in the church of St Andrews at Greensted-juxta-Ongar, now the oldest wooden church in the world. This church is over 40 miles away from Bury St Edmunds, which means that whatever was on Angel Hill before it became Edmund’s shrine, it was not local to the place of Edmund’s martyrdom, nor was it his capital, and so must have been a place with prestige worth the journey. The abbey was built as a shrine to Edmund, and the town seems to have grown from there. King Edmund became the patron saint of England, before being demoted by followers of Saint George. The place chosen to be his shrine must surely have been important before he died.

One abbot of the church at Bury St Edmunds was Anselm, nephew of the famous philosopher by the same name. He started out in the Abbey of San Michele in the Italian Alps, before becoming an abbot in Rome, and then Bury St Edmunds. He rebuilt the church there, originally dedicated to Saint Denis, and re-dedicated it to Saint James, as he was unable to go on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, the shrine of St James the Apostle. Anselm also rebuilt the church of St Mary 200 metres away, on a different hill named Honey Hill. This church was 7th century, and had been originally built by the first English king to be a Christian, named Sigeberht, who eventually became a martyr and a saint. This church was the grandest of the three parish churches of the town, (the others being St James and St Margaret), and the queen of France Mary Tudor was buried there. In view of the fact that the alignment of sites from St Michael’s Mount to Avebury goes through many churches dedicated to Mary, this particular church, on a hill, fits in very well. Perhaps at some point in the distant past the parish churches of James and Mary on Angel Hill and Honey Hill were temples to deities similar to Apollo and Artemis, Sun and Moon, or Jupiter and Venus.

It has been suggested that while the ‘Michael’ line that runs across southern England goes through Bury St Edmunds, the city itself has no church dedicated to the Archangel Michael and there cannot really be connected. However, the presence of a cathedral on this alignment is already an indication of the site’s importance. Further more, the cathedral is on a hill. Churches and burrows on hill tops have been a characteristic of the alignment so far. This hill is called Angel Hill. If this alignment exists, if it is a thing to be understood, to be grappled with, then surely it must be looked at as something that is at least as old as Avebury. We can hardly expect all ancient sites along the alignment to have been given dedications to the Archangel Michael or to Mary, or even for those dedications, if they did one exist, to have been preserved until today. In any case, insisting on considering only churches dedicated to St Michael to make up the alignment when there are obviously many significant sites that are much much older than these churches seems a little strange. Why focus only on the Norman churches? The cult of St Edmund is obviously pre-Norman anyway, and though St George came along to take St Edmund’s place in English hearts, St Edmund would surely have remained an important figure for centuries after 1066, too important to have his shrine renamed. The Mont Saint-Michel was named after the Archangel quite early on, in the 8th century, by a bishop inspired by an Italian shrine, and there was a possible 9th century link between Skellig and an angel, but it’s not clear whether Saint Michael’s Mount and Skellig Michael were dedicated to Michael before the Norman conquest. It could be that, in the British Isles and Ireland, the building of churches dedicated to Michael was a Norman thing. Saint Michael was the Norman patron saint.

The churches on the hills in Bury St Edmunds could mark the sites of long gone temples. It does seem that the alignment beyond Avebury to the north east is mostly associated with Mary, not so much Michael, and there is a beautiful church to St Mary right next to the cathedral in Bury St Edmunds. Perhaps the presence of a major religious site, whatever the religion, whatever the dedication, can be interpreted as potentially significant if it is right on the line, in the knowledge that sacred buildings are often built on top of the remains of sacred buildings.

Beyond Bury St Edmunds, there are quite a few churches dedicated to St Mary or Michael near or on the line. There are many more in the general vicinity, not all on the line of course, but many are within a mile or so of it.

The first church is St Mary’s at Pakenham:

The churches of St Mary at Rickinghall and at Rushton are on the line.

After Rushton the line goes through the Church of St Mary’s in Denton, Bungay, Ellingham, Haddiscoe, and Ashby. At Bungay the brown line from Carn Lês Boel to the north side of Avebury extended goers right through the castle in the town, a ruined Norman building on a mound named Bigod.

The Church of St Michael at Broome is about half a mile from the line, as is the Church of St Mary at Ditchingham.

Before having a look at what lies beyond the east coast of England for this line, it’s worth looking to see if there are any patterns or interesting distances between sites so far along the Michael alignment.

The English Michael line beyond England?

Beyond the sea, what then? I traced the lines from St Michael’s Mount to the north west and south east edges of Avebury, and the Carn Lês Boel line to the north west side of Avebury line, and extended them as far as Australia, just to see what was there. There were a few interesting places. I don’t know if they are interesting or concentrated enough to consider the English Michael line as extending beyond England, but equally I thought it would be a shame not to mention them. In fact, I extended the line all the way right round the globe, passing through Tiwanaku in Bolivia.

In Germany, where the line arrives after crossing the sea, the line goes through a group of megalithic structures, barrows and passage graves, at a village called Schwabstedt, just north of a meander of the River Treene. The next place of interest is a UNESCO site: a cluster of barrows near the village of Dannewerk. Then there’s a destroyed passage grave at Busdorf and and a couple of rune stones, and near a passage grave at Bohnert Steingrab, another at Missunde.

The line then travels through Denmark, Latvia, Russia and China. Klekkende Høj is a passage grave with a double chamber and two entrances.

Other possible sites are: Suzdal is one of the oldest towns in Russia, with many important historical monuments and archaeological sites, some of which are listed with UNESCO. The 13th cathedral is dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin and was built on the site of an earlier church. The Begazy Complex is a necropolis made up of several Bronze Age burial sites, menhirs, settlements, ancient mines and smelting places, which are from the Begazy-Dandybai culture, in the mountain valleys of central Kazakhstan. The Shorchuk or Qigexing Temple is a ruined compound of Buddhist sites, and was once a major religious centre, on the northern route of the Silk Road. In prehistory Qigexing was part of the city state of Arsi or Agni, now known as Karasahr or Qarasheher. A Buddhist monk named Faxian visited the area around the year 400 and mentions the presence of about four thousand monks who were practicing Hinayana Buddhism. Another monk, named Xuanzang, who lived in the 7th century, says there were ten Buddhist monasteries with two thousand monks. Dzongsar Monastery, is in Sichuan, China, though historically it was in the Kham region of Tibet. It was founded in the 8th century, in the native pre-Buddhist religion. It was destroyed in 1958, in the cultural Revolution, but then rebuilt in 1983. Palpung Monastery is one of the most important and influential monasteries, it’s is the historical seat of the successive incarnations of the Chamgon Kenting Tai Situpas. The monastery once hosted more than 1000 monks and had one of the most leading monastic universities of the area and has a huge library. It was also partially destroyed in the 1950s. Another monastery is Yarchen Gar, a Tibetan Buddhist monastery is mostly populated by nuns, who are being forcibly removed and tortured and re-educated. It was once the largest concentration of monastics in the world. But ultimately, whether the Michael alignment extends beyond the North Sea is open to question.

Sunrise at a Phi point between the equilux and the summer solstice

Why This Orientation? The Phi Point and the Sunrise on the Cornish Coast

The extraordinary linearity of the Saint Michael alignment, from Saint Michael’s Mount to Avebury and on toward Bury St Edmunds, raises a fundamental question: why this particular orientation? It turns out this question may not just have a geographical answer, but also a celestial one. As we trace this line across the map, its direction, its azimuth, or the angle it makes from due north, is incredibly consistent. From Saint Michael’s Mount to The Hurlers, Glastonbury Tor, Burrow Mump, Avebury and even Bury St Edmunds, the azimuth hovers very close to 58.8°, varying only slightly between sites.

But this same angle also has astronomical significance. On the southern Cornish coast, the sunrise azimuth around mid-May, specifically on the 14th or 15th of May, matches this alignment almost exactly. This date is neither the spring equinox nor the summer solstice, but sits at a golden point between them: a Phi point.

What Is a Phi Point?

In geometry, the Phi ratio, or Golden Ratio (approximately 1.618), represents a principle of natural harmony and balance. It's found in everything from seashells to galaxies, and has long been associated with sacred architecture and cosmic order. When we divide the time between two solar events, say, the equilux (the date of equal day and night) and the solstice (the longest or shortest day), according to the golden ratio, we get two special points in the seasonal cycle.

The equilux, the day when day and night are actually of equal length, with 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness, falls around 17th March. This is not quite the same as the equinox, which is when the sun crosses the celestial equator (usually around March 20th and September 22nd). Due to atmospheric refraction and the size of the solar disc, the actual day of equal light and dark often falls a few days before the equinox in spring.

The summer solstice begins on 21st June. Traditionally, the solstice was seen as a three-day event, with the sun appearing to "stand still" (sol = sun, stice = stand still) at its highest point before beginning to descend again.

A Phi point between them (the date that divides the period from equilux to solstice according to the golden ratio) falls around 14th –15th May. The Phi Point refers to a date that divides the time between these two key calendar points, defined by light to darkness ratios, the equilux and the summer solstice, according to the golden ratio (Phi).

The Golden Ratio, denoted by the Greek letter φ (Phi), is approximately 1.60834. When we apply the golden ratio to a time period, we divide it in such a way that the longer part is to the shorter part as the whole is to the longer. It is considered a symbol of natural harmony.

From March 17th to March 31st, there are 14 days, April has 30 days, May 31 days, and from June 1st to June 21st there are 21 days. This gives a total of 96 days between the equilux and the start of the solstice. To divide this period using the golden ratio, we want to find the date which is 96 days ÷ 1.618 ≈ 59.34 days after the equilux. This is May 14th or May 15th.

The point on the horizon where the sun first appears at dawn changes gradually as the year progresses, from solstice to solstice. And at Saint Michael’s Mount and Carn Lês Boel, the sunrise on these days rises at an azimuth between 58.4° and 58.9°, matching almost perfectly the alignment toward Glastonbury, Avebury, and beyond.

Date | Sunrise Azimuth |

13 May 2025 | 59.27° |

14 May 2025 | 58.85° |

15 May 2025 | 58.44° |

This close match between solar geometry and terrestrial alignment may not be coincidence. It suggests that the Saint Michael line was not simply a line between places, but a line between earth and sky.

Symbolism in the Saints: Serpent-Slayers and Solar Heroes

The significance of this orientation deepens when we consider the mythological figures associated with these sites. Along the line are churches dedicated to Saint Michael, the archangel who defeats the dragon. Others are dedicated to Saint George, another dragon-slayer. And several more are to Saint Mary, traditionally associated with the moon, perhaps representing a balance between solar and lunar forces. There is one more saint worth mentioning here: Saint Patrick, whose feast day is March 17th, the date that marks the equilux, probably stood in for a demoted solar deity, as did Saint Michael also, in all probability. Saint Patrick is famously depicted banishing snakes from Ireland, an echo of Saint Michael’s dragon-slaying role. In fact, in a medieval manuscript from the German monastery of Regensburg, Saint Patrick is said to have aided Saint Michael in defeating a sea monster off Skellig Michael, one of Ireland’s most dramatic island monasteries. Elsewhere in Ireland, Patrick is credited with defeating other monstrous forces, such as at Lough Derg, another powerful pilgrimage site with connections to the underworld and the afterlife.

Could Saint Patrick, like Saint Michael, be an early Christian re-imagining of a symbolic guardian of these liminal spaces, where cosmic order meets earthly form? And could his feast day’s link to the equilux embed him in the same system of symbolic solar geometry that appears to shape the Michael alignment?

The fact that March 17th, widely celebrated as Saint Patrick’s Day, coincides with the equilux (equal day and night) is significant. Was Saint Patrick originally linked to a solar calendar event? If we compare the symbolism of Saint Michael and Saint Patrick, we find striking similarities between them:

Both are depicted slaying a serpent or dragon, Saint Michael in Christian iconography and Saint Patrick in Irish tradition. Saint George also fits this description, and there are several churches dedicated to Saint George along the alignment.

Both Saint Patrick and Saint Michael are associated with hilltop sites and rocky places. We can think of the Saint Michael’s churches on top of Saint Michael's Mount, Glastonbury and Burrow Mump, but also further afield, in France, the Mont Saint-Michel, and on top of a volcanic plug, at Le-Put-en-Velay, are two striking examples. Saint Patrick is also associated with such places, for example at Cashel, ...and Patrick’s pilgrimage to Croagh Patrick.

Saint George, Saint Patrick and Saint Michael are all very important figures, being the patron saints of England, Ireland and France. This suggests a common trait, perhaps standing in for long lost divine figures, whether or not Saint Patrick and Saint George were real historical people. Patrick’s Day marks the equilux.

The way these saints are depicted, slaying a dragon or devil, or standing on snakes, links them all to the constellation Ophiuchus, the Serpent-bearer. This constellation is a key constellation, not one of the 12 of the official zodiac, but which has a foot in the line of the ecliptic, and a foot in what we perceive from earth as the Milky Way (though we are in the Milky Way also). Furthermore other divine figures are associatedwwith features of this constellation, from the Virgin Mary, to Horus, etc

In the following sections, we’ll explore whether this pattern, this union of land, myth, and celestial geometry, appears elsewhere: across Britain, Ireland, and even France. But already, the alignment that runs from Cornwall to East Anglia seems to encode a striking convergence of divine symbolism, astronomical precision, and sacred geography, a legacy as rooted in stone as it is in the stars.

Context: A Grand Landscape Geometry

The Saint Michael alignment, linking many sacred and ancient sites, reveals a striking precision in its geometric and astronomical alignments. It's helpful to situate this alignment within a broader landscape, as this phenomenon of places connected to other places over great distances is not an isolated phenomenon. Across Britain, Ireland, and France, and beyond, key locations, including Stonehenge, Avebury, the Mont Saint-Michel, Durham Cathedral, Saint Michael’s Mount, Rouen, and Thornborough Henges, form a coherent structure tied to celestial movements, ancient measurements, and the golden ratio (Phi). The numerical relationships in distances, azimuths, and daylight ratios suggest an intentional and sophisticated landscape design, challenging conventional understandings of these sites.

Saint Michael’s Mount: A Nexus of Alignments

Saint Michael’s Mount holds a pivotal position in this network. Its geographical and astronomical significance emerges through precise sunrise azimuths and Phi relationships.

While the Saint Michael alignment captures our attention with its consistent azimuths and solar resonance in May, a second thread weaves through Britain’s ancient landscape: one that leads directly to Stonehenge, perhaps the most enigmatic monument of them all.

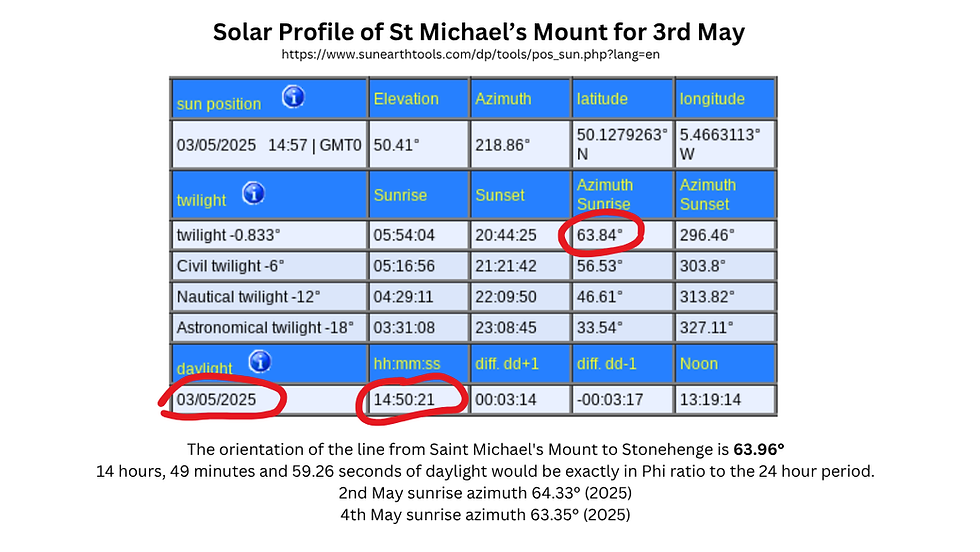

The Stonehenge–Saint Michael’s Mount Line: May 3rd and the Phi of Light

One more line deserves mention here: Stonehenge lies exactly along the 63.84° azimuth from Saint Michael’s Mount, which corresponds to sunrise on May 3rd as seen from the mount. If we draw a line from Saint Michael’s Mount, along this azimuth, it will arrive precisely at Stonehenge (azimuth: 63.84°) What is the significance of the 3rd of May? Once again Phi, the golden ratio comes into play. Daylight duration on May 3 at Saint Michael’s Mount (14h 50m 21s) is in Phi ratio with a 24-hour day, reinforcing its astronomical importance. In this sense, the 3rd May is summer Phi-day, by virtue of the ratio of day to night on that date.

This day represents a "Phi day of light", where sunlight itself embodies the sacred proportion. That it marks the sunrise direction toward Stonehenge is likely no accident.

Stonehenge: May Day and the Station Stones

According to a reconstruction by C.A. Newham, featured in Robin Heath’s Stonehenge: Temple of Britain, the diagonal axis of the Station Stone rectangle at Stonehenge aligns with the sunset on May 1st (Beltaine) and August 5th, and with sunrise on November 5th and February 5th. These are approximately the four cross quarter days of the year, key moments in the ancient calendar.

These dates are Phi days, but of a different sort as previously encountered. This kind of Phi day means the ratio between daylight and darkness on these days is either Phi or Phi squared. If daylight and darkness are to be in Phi ratio, in a 24 hour period, one needs to be 14 hours and 50 minutes, and the other needs to be 9 hours and 10 minutes. For convenience, we can refer to these types of dates as Phi days of light, as opposed to phi points between two events.

At Stonehenge, May 1st isn’t just Beltaine, the start of summer in the Celtic calendar. It also marks a point where day and night are in the golden ratio, as it is at Saint Michael’s Mount on May 3rd. The Book of Enoch deals with day to night ratios, though not in relation to Phi, but in terms of divisions of the 24 hour period into 18 parts. However, this shows an ancient concern for thinking in terms of day to night ratios. This balance of light and dark, rooted in a mathematics of harmony, may explain why Stonehenge occupies such a significant place in both landscape and lore.

At Stonehenge's latitude, the value of the winter Phi day sunrise at Saint Michael's Mount orientates the Station Stone rectangle: the North South line runs through the rectangle in such a way as to create an angle between the North-South axis and the longer side of the rectangle which closely matches Phi winter sunrise at Mont Saint-Michel. And this rectangle is itself perfectly oriented to summer and winter solstices and to lunar standstills (which, uniquely at this latitude, form a right angle with each other). 12 November 09:12:19 117.07°

13 November 09:09:17 117.52°

117.56° is close to the azimuth of the diagonal in the station stone rectangle: 117.574°. So I think it is possible to put forward the idea that this diagonal corresponds to the position of the sun at dawn on a day when daylight and darkness are in Phi ratio at Stonehenge, in winter.

15th May: A Line from Stonehenge to Saint Albans

Extending a line northeast from Stonehenge at an azimuth of 57.69° leads directly to St Albans Cathedral, the site of the martyrdom of Saint Alban, Britain's first recorded Christian saint. His execution took place on the hill where the cathedral now stands, once home to the Roman city of Verulamium, itself built beside a Celtic sacred site.

This azimuth corresponds to sunrise on May 15th, 57.63°, a Phi point between the March equilux and June solstice, at Stonehenge, once again tying golden ratio geometry to the solar year, a moment of equilibrium tipped toward the full light of summer. That this line from Stonehenge to St Albans matches this solar geometry so precisely suggests that even as Saint Michael's line tracks the sunrise on this date, Stonehenge may serve as a solar observatory for it as well.

Michaelmas, Skellig, and the Solar Cross of Autumn

Further west lies another dramatic outcrop: Skellig Michael, the Irish island monastery named after the archangel. On September 29th, Michaelmas, sunrise at Skellig aligns with an azimuth of 92.69°, almost identical to:

Skellig Michael → Stonehenge: 92.80°

Stonehenge sunrise on September 29th: 92.65°

While the line drawn from Skellig along the sunrise azimuth for Michaelmas does not hit the famous stone circle precisely, it passes within a mile of it, between the Great Cursus and Durrington Walls, key parts of the larger Stonehenge ritual complex. Given the precision of solar motion from sunrise to sunrise, and the long distance involved, the margin of error here is negligible. The previous day, the 28th September, has a sunrise azimuth of 92.06, and the following day has an azimuth of 93.32 which are both way off. If you draw lines for both of these days, and measure the distance between them in the Stonehenge area, they are 8.3 miles apart. So each of these sunrise lines from Skellig, 28th, 29th and 30th September, projected all the way to Stonehenge is just over 4 miles apart from the next in terms of a north-south measure at the meridian going through Stonehenge. In effect, a 29th September sunrise azimuth is as good as it gets to link Skellig with Stonehenge.

The feast days of saints usually mark the day of their death, often through martyrdom. While Saint Michael is called a saint in the Christian tradition, this being, neither male or female, is in fact an archangel. But how does a non-human entity have a feast day? Or, for that matter, several feast days? What exactly do the dates correspond to? Michaelmas must mark an event in the sky. Here, with sunrise at Skellig Michael, Michaelmas emerges not only as a Christian feast, but also as a solar hinge in the ancient landscape, binding together sacred sites through the turning of the year.

Brussels, Aachen, and the Continental Line

The solar link from Stonehenge on Michaelmas continues beyond the British Isles.

Drawing a line from Stonehenge at 92.65°, the sunrise azimuth for September 29th, brings us to the Grand-Place in Brussels, less than half a mile off.

Just to the north stands Brussels Cathedral, dedicated to Saint Michael and Saint Gudula, patron saints of the city.

A line from Brussels Cathedral to Aachen Cathedral, the Carolingian heart of Europe, has an azimuth of 93.16°, again aligning with the Michaelmas sunrise in Brussels (92.63° on September 29th). The azimuth from Stonehenge to the Grand-Place is in fact 92.47° and to the cathedral 92.45°. Sunrise azimuths for the previous and following days are 92.03° and 93.27°, so in fact the Michaelmas sunrise azimuth from Stonehenge is in fact the best fit for Brussels.

A sunrise azimuth for the 29th September in Brussels is 92.63°. A line drawn from the cathedral along this orientation goes to Aachen, Aix la Chapelle. The Brussels Cathedral - Aachen Cathedral line is in fact 93.16° and 75.68 miles. The sunrise azimuths for the previous day is 92.01°, and the following day, 30 September, is 93.24°, so the 29th September is the best fit for a sunrise in Brussels to line up between the two cathedrals, St Nicolas and St Michael in the cathedral in Aachen.

This alignment, moving from Stonehenge to Brussels to Aachen, ties together prehistoric sanctuaries, Christian relics, and solar geometry, all along the Michael axis.

The Golden Triangle and the Lunar Connection

But Stonehenge’s power is not just in its solar logic. The monument is also deeply entwined with lunar cycles, and here again, it links with the great Michael sites to the southwest and across the Channel.

A nearly perfect isosceles triangle connects:

Stonehenge

Saint Michael’s Mount (Cornwall)

Mont Saint-Michel (Normandy)

This triangle reflects a 6:6:7 ratio, a number pattern that aligns with the Metonic cycle, the period of 19 years (6+6+7) over which lunar phases realign with the solar year. The distances are equally compelling:

Stonehenge to each Mount: ~176.3 miles

Mont Saint-Michel to Saint Michael’s Mount: 206.14 miles

If this triangle were a perfect golden triangle, its height would be 142.65 miles—a mere 0.35% off from the actual 143 miles.

This blend of Phi geometry and lunar rhythm implies more than coincidence. It suggests that these three sites may have been placed with interlocking solar and lunar functions in mind, encoding the heavens in the earth.

Also, Stonehenge is at the centre of a large circle linking Saint Michael's Mount, The Mont Saint-Michel, the ilot Saint-Michel off the coast of Brittany, which ahas a chapel dedicated to Saint Michael on it, and the abbey and cathedral of Rouen, in France.

The Golden Triangle and Metonic Cycles

The Stonehenge–Michael Mounts triangle encapsulates fundamental mathematical relationships: a 6:6:7 triangle links Stonehenge, Mont Saint-Michel, and Saint Michael’s Mount, reflecting the lunar Metonic cycle (19 years). The distance between Stonehenge and the Michael Mounts (206.14 miles) aligns with phi and pentagonal geometry. If a perfect golden isosceles triangle were formed, its height would be 142.65 miles—astonishingly close to the actual 143 miles. Stonehenge–Michael Mounts’ distances mirror 12 lunations, linking lunar and solar cycles.

In Summary

Whether it is:

May 1st, or Beltaine, being a date on which daylight and night are in Phi ratio at the precise latitude of Stonehenge, and the Station Stones reflecting the angle of sunrise on that day

Sunrise on May 3rd’s at Saint Michael's Mount, when day and night are in Phi ratio at that latitude, the azimuth of sunrise leads to Stonehenge

Sunrise at Stonehenge on May 15th, a Phi point between the spring equilux and the summer solstice, gives an azimuth which leads to Saint Albans

September 29th’s Michaelmas sunrise from Skellig giving an azimuth which leads to Stonehenge

September 29th’s Michaelmas sunrise from Stonehenge giving an azimuth which leads to Brussels, which has a cathedral of Saint Michael, and from there a Michaelmas sunrise azimuth leading to Aachen.

The precise circle centred on Stonehenge which runs through Saint Michael's Mount, the Mont Saint-Michel, and the cathedral and abbey at Rouen

…we see again and again that Stonehenge stands at the nexus of solar geometry, sacred architecture, and spiritual symbolism. This is not merely a monument, it is a cosmic instrument, tuned to the rhythm of light and time, and carefully positioned within a broader web of meaning stretching from Ireland to France.

Major Alignments and Distances

The distances between key sites suggest an overarching design:

Saint Michael’s Mount to Stonehenge: 176.45 miles (azimuth 246.79°).

Mont Saint-Michel to Stonehenge: 176.3 miles (azimuth 175.3°). The difference between the Mont Saint-Michel–Stonehenge and Saint Michael’s Mount–Stonehenge distances is just 729 feet (0.0078%), highlighting intentional placement.

42 300 x 264 / 63360 = 176.25

Saint Michael’s Mount to Mont Saint-Michel: 206.14 miles (azimuth 118.32°).

The distance between Saint Michael’s Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel is almost exactly 10 / 6 of the distance between Stonehenge and Lundy. The distance between each of the two Michael Mounts and Stonehenge is exactly 10 / 7 of the distance between Stonehenge and Lundy.

Distance in miles between Saint Michael’s Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel as:

(1 lunation in days/phi) squared x 1 / phi

(Solar year / 12 lunations) x 200 = distance in miles between Mont Saint-Michel and Saint Michael’s Mount

Durham Cathedral to Skellig Michael distance = Durham Cathedral and the Mont Saint -Michel distance: equivalent to approximately (20 x Solar year / 12 lunations)² miles

The English and Irish Michael Lines

The alignments suggest a structured system of sacred geography:

English Michael Line:

Saint Michael’s Mount to Glastonbury Tor: 58.70°.

Saint Michael’s Mount to Avebury: 58.82°.

Saint Michael’s Mount to The Hurlers: 58.31°.

Best fit for a sunrise along this alignment: May 15 (58.64°), reinforcing phi timing.

Irish Michael Line:

Skellig Michael to the Rock of Cashel, passing over two of Ireland’s highest peaks, extends to Anglesey, forming a parallel system to the English Michael Line.

Skellig Michael to Durham Cathedral: 57.21°, linking to Dublin’s historic centre and Trinity College. The Skellig - Dublin - Durham line is oriented to sunrise on the 15th May. Here we have another important alignment on a 15th May sunrise. at Stonehenge, the summer Phi day is in fact the same as May Day. So this is the latitude at which the celebrated May Day has phi ratios of daylight to darkness.

Durham Cathedral and the Michael-Meridian Connection

Durham Cathedral’s role in the alignment is crucial:

The Mont Saint-Michel–Durham Cathedral line (359.65°) runs almost perfectly north, passing through Thornborough Henges.

Durham Cathedral is nearly equidistant from Mont Saint-Michel and Skellig Michael (424.33 miles vs. 425.11 miles).

Stonehenge to Durham: 248.83 miles, 1/100th of Earth’s meridian circumference (24,883.2 miles), linking these sacred sites to global geodesy.

Skellig Michael and the Mont Saint-Michel are the same distance from Durham Cathedral. The historic centre of Dublin is on the Skellig Durham line, and the Thornborough henges are on the Durham Mont Saint-Michel line. Skellig Michael, Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont saint Michel are almost aligned.

Durham Cathedral is at the centre of a circle that goes through Skellig Michael and the Mont Saint-Michel. A line drawn from Durham Cathedral to Saint Michael's Mount passes through the island of Lundy. a line drawn from Durham Cathedral to the Mont Saint-Michel goes through the Thornborough henges. A line drawn from Durham Cathedral to Skellig Michael goes through Dublin's Trinity College and near St Patrick's Cathedral.

The Mont Saint-Michel to Avebury Line

The eastern side of the Avebury henge is precisely aligned with Old Sarum, Salisbury and the Mont Saint Michel, on a line with an azimuth of 175.41.This line runs very close to the Avebury Stonehenge line, azimuth 176.32. The line from the eastern side of the Old Sarum henge to the Mont Saint Michel runs straight through the cathedral in Salisbury, which was moved from Old Sarum to Salisbury.

Why was the cathedral moved? What did the Norman bishops know about this alignment? Did they try to preserve it by placing the new cathedral on it? Was the move entirely to do with getting out of the cold winds on Old Sarum? What was the point of that story about the white deer that was shot and finally fell on the spot of what is now Salisbury Cathedral? Perhaps that this alignment was known to them and was important to them.

The English Saint Michael alignment is just one of many 15th may sunrise lines

There are several 15th May alignments, for example Skellig to Dublin and Durham (and Durham Cathedral is significant in that it is the same distance from Mont Saint-Michel as is Skellig Michael, and also almost perfectly North of the Mont Saint-Michel), Saint Michael's Mount to Glastonbury and Avebury. There are also 15th May alignments from Rouens Cathedral to Amiens Cathedral, from Tumulus Saint-Michel to Kerkado Tumulus and Rennes, and from Kermario to Rennes Cathedral, and from Chartres Cathedral to Meaux Cathedral. There is a whole network to be uncovered, and which, for the most part, survives only in medieval religious buildings, but the network itself has to be as old as Stonehenge.

This suggests a transmission of knowledge over centuries, as some of these places are definitely of Neolithic importance, and others are medieval churches and cathedrals. Was this network laid out thousands of years ago, and remembered as a whole, with its logic, or were the individual places that formed part of the network simply re-adapted to Roman, and then Christian times, and knowledge of the system as a whole lost? The overwhelming evidence, precise azimuths, Phi ratios in daylight hours, near-identical distances, and alignments of cathedrals and prehistoric sites, suggests that the Saint Michael alignment was an intentionally crafted, vast geodetic and astronomical landscape. Whether designed by ancient civilisations with lost knowledge of Earth’s dimensions, or reflecting natural harmonic principles recognised over millennia, this network continues to amaze and challenge our understanding of sacred geometry and landscape planning.

Conclusion

One of the most striking findings in this study is the correlation between the alignment and the sunrise azimuth on the 14th/15th of May. The date marks a Phi point between the equal day and night of March and the summer solstice. This suggests a possible intentional design, where ancient cultures may have aligned key sites to these specific solar events.

Looking at the broader picture, the alignment seems to weave together elements from different time periods. The presence of prehistoric stone circles, Iron Age hillforts, and medieval Saint Michael churches indicates a long-standing reverence for this pathway. While some sites, like the Hurlers and Avebury, date back to the Neolithic and Bronze Age, the medieval Christian additions suggest a later re-adoption of this sacred geography.

The alignment from Saint Michael’s Mount to Avebury is more than just a straight line on a map. It is a thread that connects different epochs, landscapes, and spiritual traditions. Whether this connection was purely symbolic, functional for navigation, or designed with astronomical precision remains open to interpretation. However, the presence of significant sites along this path, the correlation with solar events, and the repeated dedication to Saint Michael hint at a deeper, possibly deliberate, design in the sacred geography of Britain.

Further research into the orientation of these sites and their connections to other alignments, such as the Carn Lês Boel-Avebury line, may reveal additional insights into the purpose and significance of this ancient network.

Notes

1 A Temple of the British Druids, With Some Others, Described, by William Stukeley,Abury, a Temple of the British Druids, with Some Others, Described, by William Stukeley—A Project Gutenberg eBook

Commentaires